Posts tagged ‘Chocolate’

WONKAnfusion: Or, Who is Buying WONKA Chocolate?

Nestle’s new WONKA line of chocolates has me a bit mystified.

Cybele in her review of Wonka Exceptionals Domed Dark Chocolate over at candyblog.net described the new product and packaging as:

[T]he quality of the chocolate is much better. The chocolate is smoother, has a bolder flavor and of course the fact that the ingredients are better should make it easier for families to choose Wonka. I’ve compared them before to Dove and Hershey’s Bliss – but what these have going for them is that the packaging is all about imagination – the bright striped foils are going to appeal more to kids than the sedate and elegant positioning of Dove or Bliss.

I agree with her description, but it seems kind of schizo to me. On the one hand, the quality of chocolate and the pricing put the Wonka line in competition with Dove and Hershey’s Bliss, chocolates that convey adult sophistication. On the other hand, the packaging is all bright colors and psychedelic swirls, more like the packaging on “extreme” kids candies.

I was confused. Who is supposed to buy these? They seem too expensive and too big for kids to buy for themselves; is it about parents who want to buy “quality” candy for their kids? That doesn’t make sense to me either: parents who are worried about the “quality” of their children’s candies are looking for organic and natural ingredients, not “premium” lines.

And as more and more reviews of the Wonka products have been circulating on the great candy blogs, my confusion has festered. Higher prices, wackier packaging, for whom?

And then my friend over at sugarpressure.com turned me on to the WONKAnation blog. And all was revealed.

WONKAnation: it’s a bus. A tour. Bands. Parties. Free candy. The WONKA Chick. Dude, its endless summer with Nerds and Gobstoppers in the mix. It’s a Twitter feed promising “instantaneous awesomeness!” It’s The OFFICIAL WONKA talkin’ about “you and your rockin’ WONKA style!”

The new WONKA isn’t about the little kiddies at all, its about that new demographic, those 20 and 30 and 40 somethings who want to rock and roll all night and party every day: kiddults.

Just like those kiddults, WONKA is grown up chocolate with attitude:

WONKA is bringing a pinch of whimsy, a bucket of imagination and something a little unexpected to the all-too-stuffy premium chocolate category.

So take your stuffy Scharffen Berger, your boring Green & Black, your dull Dove. WONKA’s in the house. Dude.

Hershey’s Kisses: Got Lawyer?

While I was researching the stories about Kisses and Buds in my previous posts, I came across a lot of interesting information, not all of which is included in the official “Kisses Facts.” And I also came across a lot of lawsuits. So here are some things about Hershey’s Kisses that you might not know:

Hershey’s churns out something like 80 million Kisses a day in three factories (Pennsylvania, California, Virginia). That’s 29 billion Kisses a year. There are 305 million people in the U.S. (more now, they just keep coming….). So figure almost one hundred Hershey’s Kisses per person—man, woman, infant, child–per year. And if you’re not eating your share, someone else is!

Hershey’s introduced variations like almonds and Hugs in the 1990s. Then in 2002 they started producing “Special Edition” flavors. These are all over the place: cookies and cream, strawberry, pumpkin spice, pickle. Oh, not pickle yet. Well, I’m sure it’s coming. Anyway, if you want to see what kinds of Kisses have come and gone, visit Zoe’s Online Hershey’s Kisses Collection. Zoe is 11 years old and has been collecting Kisses for five years. She maintains a lovely online collection of more than 55 Kisses flavors. I had no idea!

Hershey’s introduced variations like almonds and Hugs in the 1990s. Then in 2002 they started producing “Special Edition” flavors. These are all over the place: cookies and cream, strawberry, pumpkin spice, pickle. Oh, not pickle yet. Well, I’m sure it’s coming. Anyway, if you want to see what kinds of Kisses have come and gone, visit Zoe’s Online Hershey’s Kisses Collection. Zoe is 11 years old and has been collecting Kisses for five years. She maintains a lovely online collection of more than 55 Kisses flavors. I had no idea!

Save the Earth, Eat a Kiss: the foil wrapper on Hershey’s Kisses is recyclable. So throw it in the green bin, or better yet, reuse it to make a fake Hershey’s Kiss. See if you can get away with it, but watch out, as our next item demonstrates.

Save the Earth, Eat a Kiss: the foil wrapper on Hershey’s Kisses is recyclable. So throw it in the green bin, or better yet, reuse it to make a fake Hershey’s Kiss. See if you can get away with it, but watch out, as our next item demonstrates.

Hershey’s Chocolate is litigious when it comes to defending their trademarks. In April 2009, they went after artisinal chocolatier Jacques Torres for a high-end truffle he was selling as “Champagne Kisses.” Each Champagne Kiss costs $1.50, for which you get a chocolate cube filled with champagne truffle (made with real Tattinger Rose Champagne) and decorated with a red lips kissing mark. Here’s what Hershey alleged:

Hershey’s Chocolate is litigious when it comes to defending their trademarks. In April 2009, they went after artisinal chocolatier Jacques Torres for a high-end truffle he was selling as “Champagne Kisses.” Each Champagne Kiss costs $1.50, for which you get a chocolate cube filled with champagne truffle (made with real Tattinger Rose Champagne) and decorated with a red lips kissing mark. Here’s what Hershey alleged:

Hershey is concerned that Jacques Torres Chocolate’s use of the mark KISS or KISSES may cause consumer confusion with Hershey as to the source, sponsorship, or affiliation of Jacques Torres Chocolate’s product.

And here’s what Torres, via his lawyer, replied:

Mr. Torres will not discontinue his use of the term “Champagne Kiss.” We believe that this is yet another example of a giant, monolithic corporation attempting to take advantage of “the little guy,” in this case, a world-renowned artisan from France. … Mr. Torres vigorously disputes your contention that he is using or infringing upon a Hershey-owned trademark. The analogy might be similar to Chevrolet complaining that Rolls Royce is infringing on the Chevrolet trademark.

Take that, Hershey! Read more: Hershey’s v. Jacques Torres: The Lawyer-to-Lawyer Slapdown! — Grub Street New York

![]() There have been cases where Hershey’s Chocolate was much more clearly protecting itself from legitimate infringers. An early case involved the Hershey Creamery, also of Lancaster, Pennsylvania; the Hershey family of the Hershey Creamery was no relation to Milton Hershey. The Creamery was mostly an ice cream business, but in the ‘teens began producing chocolate candy and cocoa. Then there was trouble:

There have been cases where Hershey’s Chocolate was much more clearly protecting itself from legitimate infringers. An early case involved the Hershey Creamery, also of Lancaster, Pennsylvania; the Hershey family of the Hershey Creamery was no relation to Milton Hershey. The Creamery was mostly an ice cream business, but in the ‘teens began producing chocolate candy and cocoa. Then there was trouble:

Milton S. Hershey learned of the candies in 1919, and assigned Charles Ziegler to “find instances of confusion and infringement and of unfair competition”. Ziegler found that in addition to making similar products, the packaging used on the chocolates resembled that used by Hershey Company—then called Hershey Chocolate. Investigating complaints from retailers in Boston, New York, Binghamtom, Norfolk, and Richmond, Ziegler reportedly found that retailers were confusing the two products, and sometimes deliberately replacing the higher priced Hershey Company products with the Hershey Creamery products. In Harrisburg, Ziegler found a display of Hershey Creamery “Hershey Kisses” which were bite-sized chocolate drops similar to the chocolate company’s creations. After cease and desist letters failed to resolve the problem, Milton Hershey filed suit in 1921 in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania for trademark infringement. In 1926, a district judged partially sided with Hershey Chocolate and prohibited the creamery from using the name Hershey’s in connection with “manufacture, advertisement, distribution, or sale of, among other things, chocolate, cocoa, chocolate confections, and chocolate or cocoa products”.

Source: Wikipedia entry for Hershey Creamery. Wiki sources: D’Antonio, Michael. “A Betting Man”. Hershey: Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams. Simon and Schuster, p. 184–185. Hershey Foods Corp. v. Hershey Creamery Co., 945 F.2d 1272 (3d Cir. 1991)

![]() A fine book on the Hershey Chocolate story is Michael D’Antonio’s Hershey: Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams published by Simon and Schuster in 2006. D’Antonio is an independent journalist, and the book is an “unauthorized” biography. That doesn’t mean it’s bad, it just means the book is not a product of the Hershey Company. So when Hershey caught wind of the book’s cover just a month before the book was to be released, they flipped out. I’m not surprised: the book looks just like a Hershey Bar.

A fine book on the Hershey Chocolate story is Michael D’Antonio’s Hershey: Milton S. Hershey’s Extraordinary Life of Wealth, Empire, and Utopian Dreams published by Simon and Schuster in 2006. D’Antonio is an independent journalist, and the book is an “unauthorized” biography. That doesn’t mean it’s bad, it just means the book is not a product of the Hershey Company. So when Hershey caught wind of the book’s cover just a month before the book was to be released, they flipped out. I’m not surprised: the book looks just like a Hershey Bar.

Hershey went to court to get an injunction to stop the publication of the book, based on a violation of its image trademarks. In the suit, they stated:

Hershey does not object to the content of defendant’s book, or to the mere use of the word ‘Hershey’ in the title of the book. However, defendant has designed and adopted a dust jacket for the book which extensively uses Hershey’s well-known marks and trade dress beyond any manner permissible under law.

Hershey didn’t win this one. The case settled out of court: the book went forward with the trademark images, but with a disclaimer on the cover that says “Neither Authorized Nor Sponsored by the Hershey Company.” As for the image of the Hershey bar, it’s up to readers to figure out they can’t eat it.

Hershey’s: Why a Kiss is Just a Kiss

Have you ever wondered why Hershey’s Kisses are called “kisses”? Here’s the official answer from Hershey’s Inc:

While it’s not known exactly how KISSES got their name, it is a popular theory that the candy was named for the sound or motion of the chocolate being deposited during the manufacturing process.

Well, as for the first part, that “it’s not exactly known,” I can’t dispute that. Hershey’s has been planting their chocolaty kisses on the collective lips of America since 1907. No one alive today was witness to that first chocolate blob, or the “eureka” moment when someone shouted “It’s a Kiss!”

But that part about the sound of the chocolate dropping onto the conveyor belt? I’m afraid I’m going to have to pop a big old hole in that bubble of a story.

The fact is, back in 1907 you had your choice of kisses. There were generic flavored kisses like Cocoanut Kisses, Molasses Kisses, Nut Kisses, simple candies that anyone might make. Then there were the fanciful brand name Kisses: Sun Bonnet Kisses (National Candy Co, Chicago); Miller’s Violet Kisses (George Miller & Son, Philadelphia); Blue Bell Kisses (Robt. F. Mackenzie Co, Cleveland), Honey Corn Kisses (Wm. J. Madden & Co NY); Nethersole Kisses, Moonlight Kisses (United States Candy Co, Cleveland); Elfin Kisses (Caldwell Sweet Co, Bangor Maine); Heckerman’s Lucky Kisses: 5 cent box “assorted selected flavors.” My personal favorite wasn’t around in 1907, but I’ll mention it anyway since we’re on the topic of Kisses. The Novelty Candy Company offered around 1915 a pack of three flavors, cinnamon, molasses, and vanilla called Tom, Dick and Harry Kisses, “the kiss you can’t afford to miss.”

So when Hershey’s came up with a little bite of chocolate, calling it a “chocolate kiss” was sort of obvious. A candy “kiss” was just another name for a small bite sized candy, typically something with a softer texture. There were lots of other names for small bite sized candy at the time: drops, buttons, blossoms, balls. There was nothing at all special in 1907 about the name “chocolate kiss.”

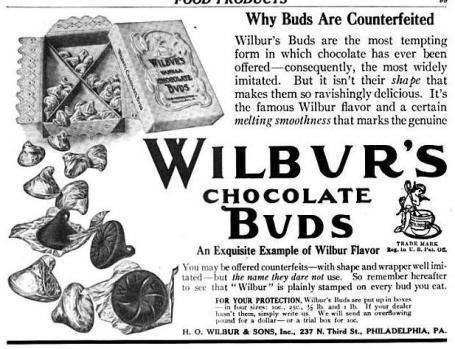

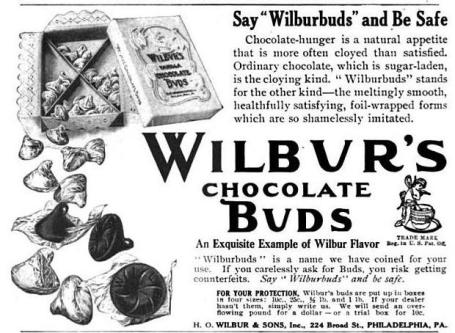

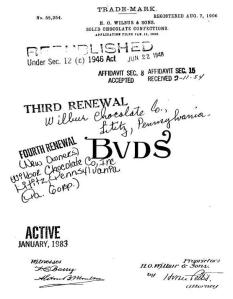

In fact, the rival chocolate company H. O. Wilbur and Sons was the one who had come up with a proprietary name for their own bite sized chocolate: Wilbur’s Chocolate Buds. Wilbur had taken the important step of trademarking the name “Bud” for its chocolate in 1906.

But just as with today’s “xerox” and “kleenex,” the term “chocolate bud” was quickly coming to mean any sort of chocolate drop, and imitators were rushing in to sell their own “buds.” Things got so bad that Wilbur went to court to get an injunction against competitors trying to pass off their look-alike products as genuine Buds. Trade magazine advertisements warned dealers against accepting imitations and insisted: “there are no buds but Wilbur’s.” Ads taken out in popular magazines cautioned candy lovers to watch out for “counterfeits” and make sure their Buds were genuine Wilbur Buds.

When people talked about “chocolate buds” in the 1900s, its pretty clear that they are talking about Wilbur’s product or something very similar. A 1914 recipe for an ice cream sundae, for example, suggests sprinkle of “chocolate buds” on top. A 1911 publication suggesting ideas for money-making proposed that a woman going into the candy business might stock her store with “the finest chocolate buds, marshmallows, and different size cakes of the best milk chocolate.”

In contrast, the term “chocolate kisses” could mean just about anything small and chocolate flavored. In addition to references to candy, I found the term in late nineteenth and early twentieth century cook books to name different sorts of cookies. And in 1910 when the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture examined 336 candy samples for purity and accurate labeling, 13 of those candies were described as “chocolate kisses,” a generic category. Only one of those candies was a “chocolate bud.”

It wasn’t until after the end of WWI that the term “kiss” seemed to be increasingly associated with the chocolate drop. The November 1919 issue of Confectioners Journal included an ad from the Racine Confectioners Manufacturing Company for the “Racine Chocolate Depositor,” a machine that was for making ” Chocolate Kisses and Stars… cast on metal covered plaques without the use of molds of any kind….plain tubes for kisses, or with tubes for 5-6-8-10-12 point stars. Then in late 1921, L. Weiscopf of New York advertised a “Chocolate ‘Kiss’ foil Wrapping Machine” and boasted that it was “in constant operation in several of the largest chocolate manufacturing plants in the United States.” This is most likely they machine Hershey’s used, a machine that also allowed them to include the distinctive paper plume peeking out of the foil wrapper.

The marketing of these specialized machines suggests that, after WWI, Hershey’s chocolate kiss had become so familiar that when candy people wanted a general term for a conical drop of chocolate, they called it a “kiss.” But the fact that these machines were sold widely also tells us that others besides Hershey’s were making and selling chocolate kisses.

“Kiss” was, for most of the twentieth century, just a generic term for a bite sized candy. This is why for 90 years Hershey’s was unable to trademark the term “Kiss” as a name they could use exclusively for their chocolate kisses. Until a the late 1990s, every trademark application for logos or wrapper images for “Hershey’s Chocolate Kisses” included a limitation: the term “kiss” was always excluded. The trademark examiners insisted that “kiss” was a general term for a sort of candy, and according to U.S. Trademark law, you can’t claim a trademark for a general term like “milk” or “tissue.”

Finally, in 2001, Hershey’s won the trademark after a prolonged legal battle (U.S. Registration 2,416,701). Henceforth, only one candy could call itself a “Kiss.” Hershey’s lawyers argued that, despite a long history of general usage, by the 1990s America was persuaded that a candy called “kiss” always meant Hershey’s Kiss, and they commissioned a huge survey to prove it. The judge sided with Hershey’s, and a kiss became a Kiss ™.

Which was first: the Hershey’s Kiss or the Wilbur Bud? Read about the candy copy cats in my previous post, “Kissing Cousins.”

Just for Fun: You can read the legal briefs filed for and against “Kiss” on the U.S. Patents and Trademarks website. From “Trademark Document Retrieval,” enter the registration number 2416701. Choose the document dated 24-Feb-2009 called “Unclassified.”

Kissing Cousins: the Hershey’s Kiss and the Wilbur Bud

Hershey’s Chocolate Kisses: do we need to say more? Everybody knows the Kiss. Hershey’s Kiss is certainly one of top contenders for “American Candy Idol.” But today, Candy Professor takes you back to a time when the Kiss was not the Kiss, back to a time when candy brands were still a new idea, and candy makers didn’t always know the best ways to profit from their candy innovations.

Hershey’s Chocolate Kisses: do we need to say more? Everybody knows the Kiss. Hershey’s Kiss is certainly one of top contenders for “American Candy Idol.” But today, Candy Professor takes you back to a time when the Kiss was not the Kiss, back to a time when candy brands were still a new idea, and candy makers didn’t always know the best ways to profit from their candy innovations.

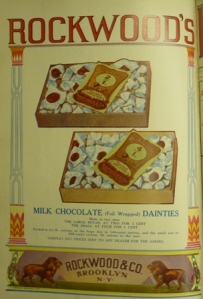

Hershey’s today is one of the major candy companies in the world, boasting annual sales in excess of $4 billion dollars. But around 1900, Hershey’s was one among many contenders for America’s top chocolate maker. The big business in chocolate at that time was not so much direct retail products, but selling various coatings and chocolate ingredients to candy makers large and small. Rivals like Stollwerck Brothers of New York and Chicago, H. O. Wilbur and Sons of Philadelphia, and Rockwood and Co.of Brooklyn were promoting their own chocolate goods, each promising purity, quality and taste unrivaled. Finished candy goods were, for many of these companies, a side line to the real action in wholesale cocoa and chocolate.

Milton Hershey was early to realize the potential for selling eating chocolate on a national scale. He developed his own technique for making milk chocolate and began manufacturing small batches in 1900. Hershey’s chocolate bars were a huge success, and he quickly expanded, moving to an enormous new factory in the town that would come to be known as Hershey, Pennsylvania in 1905. The first full year of manufacture in the new factory, sales of Hershey’s chocolate products topped $1 million; that’s about $24 million in today’s dollars.

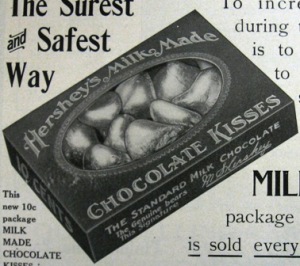

By 1907, the year the Kiss was introduced, sales had doubled to $2 million. Even then, Hershey was a major player. But other chocolate houses had their own eating chocolate products. And when Hershey came up with the “Milk-Maid Chocolate Kiss” back in 1907, it wasn’t the only foil-wrapped chocolate bite in town.

Rival chocolate manufacturer H.O. Wilbur and Son had been selling a bite-sized foil-wrapped conical chocolate drop called the “Wilbur Bud” since 1894. You wouldn’t know it today, but back in the 1900s, Wilbur set the standard for those little foil-wrapped chocolates. The candy journal International Confectioner waxed rhapsodic over the beauty and hygiene of Wilbur’s candy in 1914:

Each piece is wrapped separately; they are packed like jewels. A large box of Wilbeurbuds can lie open several days before it is all eaten. … Our little Wilburbuds can’t go stale–each is wrapped in foil.

It was Hershey that was the copy cat.

It was Hershey that was the copy cat.

And Hershey wasn’t the only one. H.O. Wilbur even went to court in 1909 to try to stop the imitators. One of these might have been Rockwood’s Chocolate Dainties, which were sold four for one cent. In their little foil wrapper, they would have been indistinguishable from Wilbur’s Buds or Hershey’s Kisses or any other similar chocolate.

Unwrapped, the Wilbur Bud was quite distinctive; the bottom of the candy was molded into a flower shape and the letters W-I-L-B-U-R embossed in each petal.

![]() In contrast, the Hershey’s Kiss then as now isn’t much to look at. It is just a plain cone, its bottom flat and unadorned. While this perhaps was less lovely to behold, it did mean the Kiss could be manufactured by dropping the chocolate on a flat belt, rather than needing special molds. This would eventually matter quite a lot, but in 1907 the Kiss’s plain-Jane looks would have been a distinct disadvantage.

In contrast, the Hershey’s Kiss then as now isn’t much to look at. It is just a plain cone, its bottom flat and unadorned. While this perhaps was less lovely to behold, it did mean the Kiss could be manufactured by dropping the chocolate on a flat belt, rather than needing special molds. This would eventually matter quite a lot, but in 1907 the Kiss’s plain-Jane looks would have been a distinct disadvantage.

The decisive moment for the Hershey’s Kiss was 1921, when new manufacturing equipment allowed the foil wrapping to be automated, and also allowed for the inclusion of the “plume” that extends from the top of every Chocolate Kiss. By spring of 1922 Hershey’s was taking out full page ads blaring “Insist upon having the “GENUINE” Sweet Milk Chocolate Hershey’s KISSES. Be Sure They Contain the Identification Tag ‘HERSHEY’S.” The plume was trademarked in 1924, meaning that no other conical foil wrapped chocolate could use the same technique to stand out.

Wilbur, and many other small American chocolate concerns, eventually fell behind Hershey in the race for market share. Milton Hershey was a generous philanthropist as well as a brilliant business man, and the success of the company in dominating the American chocolate scene is a fascinating story of doing well by doing good. Today, Hershey’s Kisses are a multi-million dollar share of the American candy market. And Wilbur’s Chocolate Buds? You can still buy them by mail-order, or out of a little Wilbur Chocolates storefront in Lititz, Pennsylvania.

So why are Hershey’s Kisses called Kisses, anyway? Read more in my next post, “Why a Kiss is Just a Kiss.”

Image of today’s Wilbur Buds from www.wilburbuds.com

Kisses image: http://www.flickr.com/photos/mtsofan/ / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Hershey’s Pieces, Brought To You By B-School

An article in the Feb 17, 2010 New York Times Business section included this quote: “I think you’re going to move into more usage occasions with this delivery method.” Jody Cook was describing:

a. Staples new Direct-to-Desk service which will restock disappearing pens on demand. The Deluxe package will also restore missing tape dispensers and staplers on a quarterly basis.

b. Dominos Pizza’s announcement that it will incorporate skateboarders and rock-climbers into its delivery fleet to expand the reach of pizza from the deepest pit to the highest wall.

c. Hershey’s new line of Pieces in Almond Joy and York Peppermint flavors, those little button siblings of Reese’s Pieces that promise endless opportunities for grabbing and going (or just sitting).

OK, that was an easy one. This is the Candy Professor, after all. But really: “usage occasions”? “Delivery method”? It makes candy eating sound like something they invented over in the business school.

So when you’re sitting with a big bag of Almond Joy Pieces in your lap, flipping the channel between Soap Net and Ice Hockey, that would be a usage occasion. And when you’re driving down the highway, looking for adventure, that would be a usage occasion. And when you’re standing in line at the bank desperately hoping that the negative sign on you statement is a clerical error, that would be a usage occasion. And wherever you are, popping those Pieces in your mouth, over and over and over, that would be a delivery method. What Ms. Cook is trying to say is “selling candy in little pieces in big bags is going to make it easier for more people to eat more candy at more times and in more places.” And that is something they came up with over in the business school.

Don’t get me wrong. I’ve got nothing against little candy bites, or candy-coated chocolate pieces, or any sort of candy for that matter. But I do feel insulted by marketers who say with a straight face, “The point [of the Pieces] is that it gives people the option to eat less and more sensibly.”

Folks, this is crazy talk. When you buy the little 80 cent bag of M&Ms or Reese’s Pieces, you eat the whole bag, right? So what happens when you put 10 oz. of candy in the bag? You’ve seen the research on potato chips: when you hand someone a bag of chips, they eat it. Big bag, small bag, doesn’t matter. Do we really think that America, having filled its collective cup holders with no-mess, no-fuss candy bits, is prepared to stop munching before all the candy is gone?

The ad campaign from Hershey’s will promote the idea that little pieces of candy have fewer calories than big pieces of candy. This as an empirical fact, but entirely irrelevant. What matters is that lots of pieces of little candy can have way more calories that one big piece of candy, and Hershey’s Pieces make it easier to forget what you’re eating. So you eat more. The marketers know this too. It’s no secret. Here’s market research analyst Marcia Mogelonsky: “Sure, half of us are going to pour the whole bag into our mouths.” Yikes.

Eat candy, but eat it with your eyes open! I’m thinking of adding a new topic to the Candy Professor course syllabus: “Mindful Candy Eating: The Buddhist Path to Sweet Enlightenment.”

Andrew Adam Newman, “Candy Makers Cut the Calories, by Cutting the Size” , New York Times Business Section, 17 Feb 2010

The Chocolate Cure

One hundred years ago, Americans had very different ideas about body image and health. Nutritional experts were worried that people were underfed and undernourished.

It was an easier time for candy lovers. Consider this account of the German “Chocolate Cure,” which ran in a 1914 journal:

In an obscure but picturesque little village of Germany there is a place called “The Chocolate Cure,” where thin people go to become stout; the patients eat and drink cocoa and chocolate all the time, while they rest, admire the scenery, gossip and grow fatter every day. The true secret of the great success of this treatment is the happy way chocolate has of fattening just the right places, settling in the hands, the neck and shoulders, making the fair patient prettier and plumper all the time. The really effective part of the cure may be tried at home by persevering women, and the medicine is so palatable and the methods so simple that there is actually, it seems, no reason why all should not be at least the desired weight.

That sound SO much more pleasurable than today’s version of the chocolate cure, which promises all the benefits of the phytochemicals and antioxidants found in abundance in chocolate, but only if you eat super-bitter 80% cacao in very small quantities, and promise not to enjoy it.

Source: “The Chocolate Cure,” Confectioners Journal Jan 1914, p. 97.

Candies We Miss: The Chocolate Sandwich

It’s too bad no one has brought back the “Sportsman’s Chocolate Bracer.”

It’s too bad no one has brought back the “Sportsman’s Chocolate Bracer.”

Imagine handing over your nickel for “two flat cakes of delicious eating chocolate which can be eaten straight or between two slices of buttered bread in the form of a sandwich.” Children’s lunch boxes would certainly be cheerier. And moms needn’t worry. A century ago, ideas about chocolate were a little less puritan than they are today. The manufacturer assured potential customers: “Consumers eat it for a food as well as for a confection, for it really has more food value than any solid chocolate for sale today.”

Well, we know better today about food value and such. But the current American equation of candy-eating with sin seems to imbue such treats as chocolate sandwiches with a demonic power well in excess of fats and sugars.

The Europeans approach the matter of chocolate sandwiches in an entirely different spirit. What we in the U.S. call “chocolate croissant” is in France “pain au chocolat,” chocolate bread, good for breakfast or afternoon snack for any petit enfant. Bakeries in France sell little chocolate bars. For les grands enfants, these come in very handy if you happen to be stumbling home around 4 am from a night at the clubs, and need a little snacky something. The boulangeries will be open at that hour, with hot bread, fresh from the oven, easy to pair with a melting piece of chocolate sandwiched inside. Italian mamas offer bread and chocolate to the bambinis for breakfast. And then there is Nutella, chocolate-hazelnut spread which is perfectly respectable any time of day, for toast, crepes, gaufres, or just out of the jar with a spoon.

Of course, the bar was not for kiddies: it was, after all “SportsMAN’s.” The bar continued to be sold after WWI, but now the emphsis was on the manly man-ness of the candy: “If you desire a change from Mild-Sweet Milk Chocolate, Try a Sportsman’s Chocolate-Bracer. A Man’s Chocolate.” (1922)

If you are looking for chocolate sandwiches here in the U.S., though, you’ll have to set your time machines for 1916: New York City, Knickerbocker Chocolate Company. Alas, a company, and a spirit of enjoyment, long gone.

Source: Advertisements for “Sportsman’s Chocolate Bracer” appeared regularly in the nineteen-teens and twenties in Confectioner International, a New York based candy trade magazine.

Where is Cadbury?

Kraft returns for round two in the Cadbury takeover bid, defending its offer of $16.7 billion by slamming Cadbury’s business prospects. According to Kraft CEO Irene Rosenfeld, Cadbury will have “limited opportunities” to create value on its own. Cadbury is the laggard in the class; he’s done his best, poor thing, but now its time to turn it all over to the professionals.

Kraft returns for round two in the Cadbury takeover bid, defending its offer of $16.7 billion by slamming Cadbury’s business prospects. According to Kraft CEO Irene Rosenfeld, Cadbury will have “limited opportunities” to create value on its own. Cadbury is the laggard in the class; he’s done his best, poor thing, but now its time to turn it all over to the professionals.

Meanwhile, the Wall Street Journal reports that Cadbury’s workers seem to be rooting for Kraft. The Cadbury factory in Keynsham, England, is slated to be closed and its jobs moved to Poland. Seems Cadbury does have some ideas for “creating value,” or at least increasing profitability (is that the same thing?) The workers believe that Kraft will somehow view the historic factory more sentimentally, and keep Cadbury chocolate in England where it belongs.

The factory in Keynsham dates to 1919; until now, Cadbury chocolate has been English chocolate, made in England. But globalization is making such “local” manufacture increasingly obsolete. U.S.-born CEO Todd Stitzer hatched the plan to close the factory back in 2007 as part of a larger market strategy. So an American is in charge of English chocolate manufacture to be moved to Poland. Where is Cadbury, anyway?

Chocolate for eating, like the chocolate bars at the heart of Cadbury, Hershey and the rest, can be formulated to many kinds of tastes. When candy was local, national chocolates were made to conform to national tastes and supplies. British preferred additional sweetness; American (Hershey’s) chocolate had a peculiar sour milky taste; the Swiss perfected a smooth balance of flavors. And Polish chocolate? Alas, the aftermath of the cold war seems to have produced a waxy, flavorless product.

Kraft promises “efficiencies,” and added value, from consolidating their existing candy lines with Cadbury. When a global powerhouse buys an English chocolate factory and moves its production to Poland to make candy that will be sold everywhere in the world, what will that taste like?

More: Wall Street Journal, “Factory Town Roots for Kraft in Candy Fight” Sept. 9, 2009